For the first half of the 20th century, Australia’s White Australia policy denied permanent residence to non-Europeans and severely limited their short-term entry.

This policy underwent a gradual change in the 1950s and 1960s, with a major reform in 1966 and a formal end to the policy in 1973, although informal discrimination wasn’t immediately ended.

The first major break came under the Coalition government led by Malcolm Fraser with the admission of a large number of refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia, close to 80,000 in the years 1977-84. By the mid-1980s, close to 40 per cent of the immigration intake was from Asian countries.

In the decades since, fringe political groups have continued to call for the re-introduction of immigration restriction, with the claim that the Australian people had never approved the fundamental change to Australia’s immigration policy. These claims ignore the reality that for nearly half a century, elections have returned governments opposed to discrimination in immigration policy on the basis of race or ethnicity.

In recent years, calls for discrimination have been primarily raised in the context of advocacy of a ban on Muslim immigration, but also with attention to problems within African refugee communities.

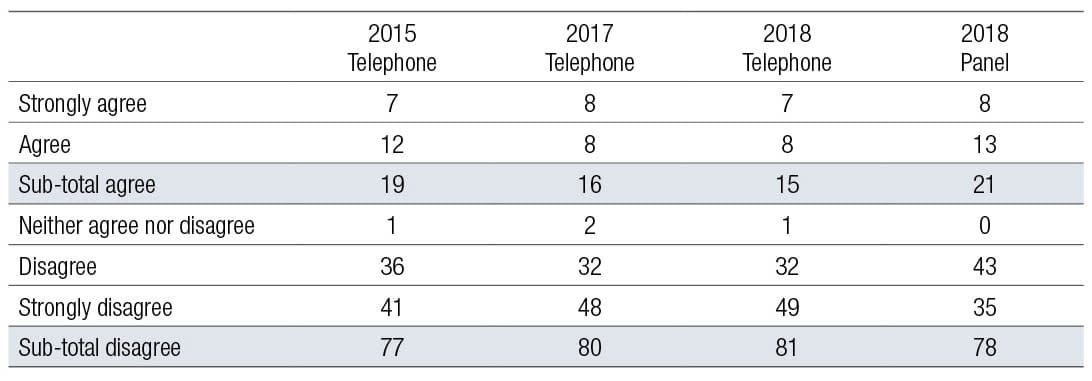

Across the surveys there has been a large measure of consistency in the rejection of discrimination – “strong agreement” with discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity is in the range 7 to 8 percent, with discrimination on the basis of religion at 8 to 11 per cent.

Senator Pauline Hanson has been a prominent advocate of discrimination, at one time focused on Asian immigrants, recently on Muslims.

Hanson’s One Nation immigration policy, which describes second and third-generation Australians as “migrants”, calls for a ban on entry from countries “that are known sources of radicalism … We cannot ignore first, second and third-generation migrants who violently reject Australia’s democratic values and institutions in the name of radical Islam”.

Former One Nation member Fraser Anning, who defected from the party following his election to the Senate and later joined Katter’s Australian Party, is a more radical exponent of discriminatory attitudes. His maiden speech in August 2018, in which he referred to the need for a “final solution” of the immigration problem, exemplifies themes current among far-right groups, whose influence in Australia has grown through social media.

Anning and the viewpoint he represents evokes an imagined harmonious society united by “common threads of inherited identity”, a time when “everyone, from the cleaners to the captains of industry, had a shared vision of who we were as a people”. His immediate objective is to “end all further Muslim immigration” and “restrict entry to those who will best assimilate”.

Surveys test claims

The Scanlon Foundation surveys provide the opportunity to test claims about public support for the reintroduction of discrimination in immigrant selection. Eleven such national surveys have been conducted since 2007, administered over telephone to respondents selected by randomly generated landline and mobile phone numbers.

In 2018, a second version of the survey was administered on the probability-based Life in Australia panel that enables self-completion of the questionnaire. The interviewer-administered survey was completed by 1500 respondents, the panel version by 2260.

Over three years – 2015, 2017 and 2018 – the Scanlon Foundation asked respondents to indicate agreement or disagreement with discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity, or religion. The questions were:

Do you agree or disagree that when a family or individual applies to migrate to Australia, that it should be possible for them to be rejected simply on the basis of …

[a] their race or ethnicity?

[b] their religion?

Across the surveys there has been a large measure of consistency in the rejection of discrimination – “strong agreement” with discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity is in the range 7 to 8 percent, with discrimination on the basis of religion at 8 to 11 per cent.

With “strongly agree” or “agree” responses combined, support for discrimination based on race or ethnicity is in the range 15 to 22 per cent; on the basis of religion, 18 to 20 per cent in the interviewer-administered version, a higher 29 per cent in the panel version.

Do you agree or disagree that when a family or individual applies to migrate to Australia, that it should be possible for them to be rejected simply on the basis of their race or ethnicity, 2015, 2017, 2018 (percentage)

Hence, contrary to the claims made by advocates of a return to the White Australia Policy, support for discrimination is not a majority position in contemporary Australia.

Support for discrimination based on race or ethnicity finds agreement at fewer than one in four respondents. There’s a marginally higher level of support for discrimination based on religion, particularly in the self-completion version of the survey, but even there, support is at less than one-third of respondents.