With the federal government’s questionable commitment to achieving a 1.5°C future, many are seeking glimmers of hope elsewhere.

Leadership on climate action is happening throughout society – youth activists, private-sector champions, and local government authorities.

Local governments are well-positioned to contribute to climate action - working at the interface between citizens, local businesses, civil society groups, and state and federal decision-makers.

Warranting urgent attention is our food system. The global food system creates more greenhouse gas emissions than any other single contributor, and is depleting precious natural resources such as land and water in the process.

In 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission called for “nothing less than a Great Food Transformation” to nourish our growing global population within planetary boundaries. Key to this transformation is a shift in population-level diets.

With nearly 70% of the global population expected to live in cities by 2050, urban local governments have a critical role to play in this food transformation.

Since it launched in 2015, the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact has attracted more than 200 signatory cities, whose mayors have publicly committed to promote fairer and more environmentally sustainable food systems within their jurisdictions.

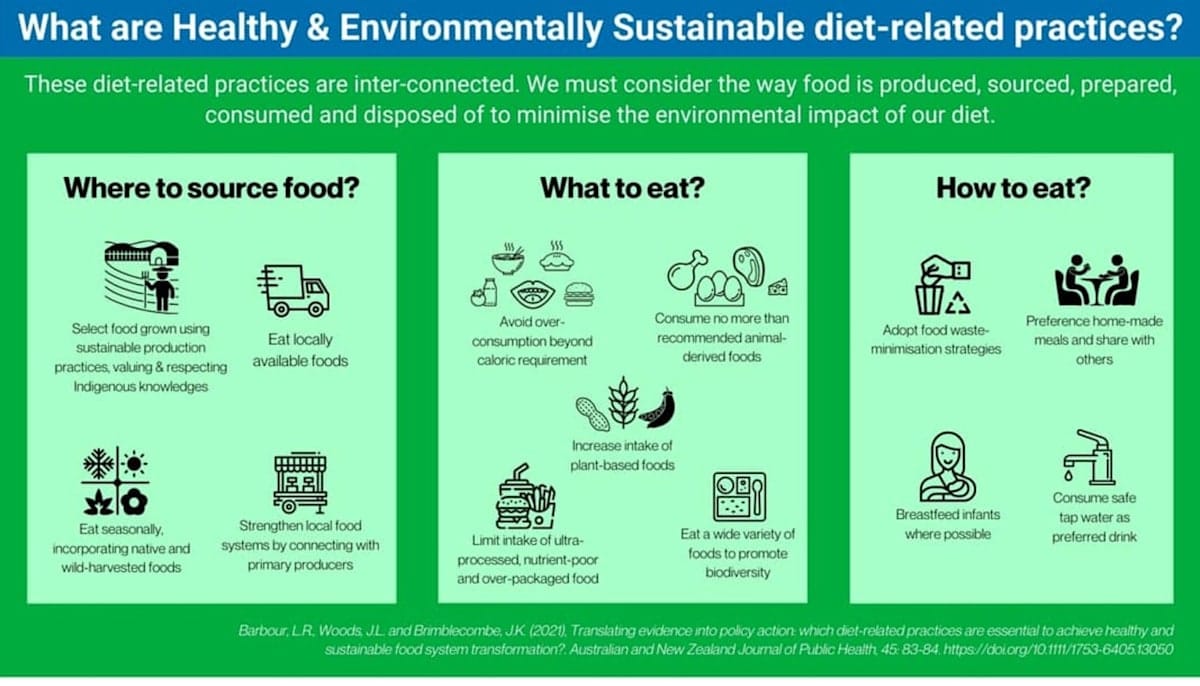

Our study, “Local urban government policies to facilitate healthy and environmentally sustainable diet-related practices: A scoping review”, mapped the policy actions being implemented by these signatory cities, which encourage their citizens to adopt the healthy and sustainable diet-related practices indicated in the graphic below.

Which recommended diet-related practices are most commonly targeted?

Local governments are focusing on those within the “where to source food” category. The least-promoted practice within these policy documents was breastfeeding; however, this doesn’t mean local governments aren’t doing work in this space. It instead suggests that the double-win of breastfeeding for health and sustainability is yet to be fully recognised by policymakers.

How are local governments promoting these practices?

Here are five examples from the 36 policy documents analysed in the scoping review:

Belgium’s Ghent en Garde food policy

If you attend a publicly-funded event on a Thursday in Ghent, you’ll only find vegetarian food. No meat can be purchased using public funds to cater for these events. And if you go to a restaurant and cannot finish your meal, you’ll be offered a compostable takeaway box, complete with Ghent en Garde’s logo.

Ghent’s local government updated its tender processes for public facilities so that all catering prioritises healthy and sustainable options. And it went one step further to prioritise suppliers who deliver goods using eco-friendly transport, and avoid single-use packaging. It also invested in social solidarity supermarkets – connecting primary food producers with people experiencing food insecurity.

Paris’ Strategy for Sustainable Food

Paris restaurant owners have been offered support and expertise to present more vegetarian menu items and, if successful, they’re awarded a prestigious “sustainable restaurant certificate”. Budding entrepreneurs can join the Smart Food Paris incubator program for sustainable food business start-ups. This includes food producers, distributors, manufacturers and retailers.

Bristol’s Good Food Plan

In the UK, Bristol’s local government produced a holistic Good Food Charter as a call to arms for partnering with stakeholders to adopt a common definition whereby “good food is not only tasty, healthy, and affordable, but also produced and distributed in a way that’s good for nature, workers, animal welfare and local businesses”.

Bristol piloted a national campaign titled Flexitarian City that incentivised local restaurants to prioritise healthy and sustainable menu items. It has a number of food waste programs for schools and hospitality, and published a citizen statement about the value of good-quality soil to the city.

Bristol also developed a pollinator strategy to promote better habitat management for insects required for food production.

Chicago’s Recipe for Healthy Places

Public health professionals are involved in all community planning efforts to avoid obesogenic decisions. Local government established restrictions on illegal dumping to protect soil health, to align with their urban agriculture efforts.

Tax incentives favour food businesses that are involved in production, processing and distribution of healthy food, and Chicago’s local government has partnered with local grocery chains in underserved areas to promote point-of-sale messages, healthy food tastings, and video messages at cash registers.

Brazil’s Sustainable Schools initiative

Brazil’s world-recognised school feeding program started in the 1940s and, while federally funded, is implemented at a local government level. In 2009, a Family Farming Law was introduced to ensure that at least 30% of the food procurement funds are used to buy food directly from local, organic family farmers.

The country’s Sustainable Schools initiative includes nutrition and food sustainability curricula, and menus are designed by nutritionists with expertise on the region’s sustainability and agricultural diversity.

So what does this mean for Australia?

Two Australian local governments, the City of Sydney and City of Melbourne, are signatories to the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, but many other local governments in Australia have been leading inspiring food system transformations for years.

For example, the City of Greater Bendigo, with its Food System strategy, is already being recognised on the global stage, named Australia’s City of Gastronomy as part of UNESCO’s prestigious Creative Cities designation.

The mantra “Think globally, act locally” has never been as critical. By localising global sustainable development targets, municipal food policy can promote healthy and sustainable diets to transform our food system, and nourish current and future generations.

This article was co-authored with Rebecca Lindberg and Julie Woods from Deakin University, and Karen Charlton from the University of Wollongong.