Dr Tim Ealey, OAM, who has died aged 93, was a small man with a big heart, and an even bigger sense of adventure. For his fourth birthday, his mother made him a cake in the shape of a boat. The little boy couldn’t have known its allegorical significance.

Tim’s life went on to become a series of epic quests and journeys that took him to the snowy wastes of the Subantarctic, the vast ruggedness of the Pilbara, and the suburban prairies of Melbourne.

He's been immortalised by having – in descending order of size – a glacier, hill and tiny rodent (Ningaui Timealeyi) named after him. This gave him the rare distinction of being able to claim that he was, indeed, both a man and a mouse.

The Monash years

Tim came to Monash as a senior lecturer in zoology in 1960 when the University was hardly more than a hole in the ground. Responding to a growing public awareness of environmental concerns, he set up classes on applied ecology and environmental conservation that eventually developed into a master’s program, despite much opposition from senior academics at the time who thought it was just about “bird-watching and bushwalking”. In a determined bid to have the subject taken seriously, he made the content difficult and cross-disciplinary, and insisted on keeping the word “science” in the title, rather than replace it with the more ambiguous “studies’’.

In 1973, he became director of the Graduate School of Environmental Science. He continued to encounter much resistance from scathing academics along the way, but was driven by a growing alarm at the planet’s diminishing resources.

The Master of Environmental Science course was the first of its kind in Australia, and one of the world’s largest. He was proud of the fact the school produced 800 graduates between 1973 and 2000 (when it closed), many of whom obtained influential positions in government and industry.

University life also provided plenty of lighter moments. He once recalled a woman ringing to say she was leaving Melbourne, and would the zoology department take her pet wombat, Wombalina? Tim kindly obliged. Several years later, the woman rang to say she was back in Melbourne for a few hours and could she possibly visit Wombalina? Tim agreed, but panicked when he subsequently discovered that the animal had died and there were no other wombats on the premises.

He made a few frantic calls and found “a mate in Frankston” who had just caught a wild one, so he sent down a car to “borrow” it for a few hours. The beast turned out to be huge, savage and male. Tim had the grim job of holding it firmly at a certain angle to disguise the fact it was most certainly male, while the “owner” fed it handfuls of grass and attempted to pet it. She left soon after, none the wiser.

Before all that though, he was born

Eric Herbert Mitchell Ealey (Tim) was born in Wentworthville, Sydney, in March 1927 to an ambitious mother, and a father physically and psychologically damaged by war. At school (Newington and Barker Colleges) he dreamt of becoming a marine biologist, gaining entry into Sydney University to study zoology. During his honours year in 1948, he successfully applied for a job with the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition on Heard Island, one of the remotest spots on Earth.

While there, he had his pants ripped by a tusked bull seal, tucked into penguin and storm petrel stew, and was attacked by an albatross that tried to drag him off a cliff. In short, he had a ball. Too young for the war, Heard Island was, he said, the place where he grew up. “It was the best thing that happened to me,” he reflected in an interview.

His research on the plankton colonies formed his thesis for a master’s in oceanography from Sydney University. Afterwards, he landed a job with CSIRO at another remote location – this time in the Pilbara on a dilapidated sheep station, Woodstock. His job was to study kangaroos, which were believed to be responsible for the rapidly declining sheep numbers.

Over the decades that followed, he lent his weight to many worthy causes. In the 1960s, he helped set up an environmental living zone at Bend of Islands, and a conservation cooperative in the Christmas Hills area north of the Yarra River.

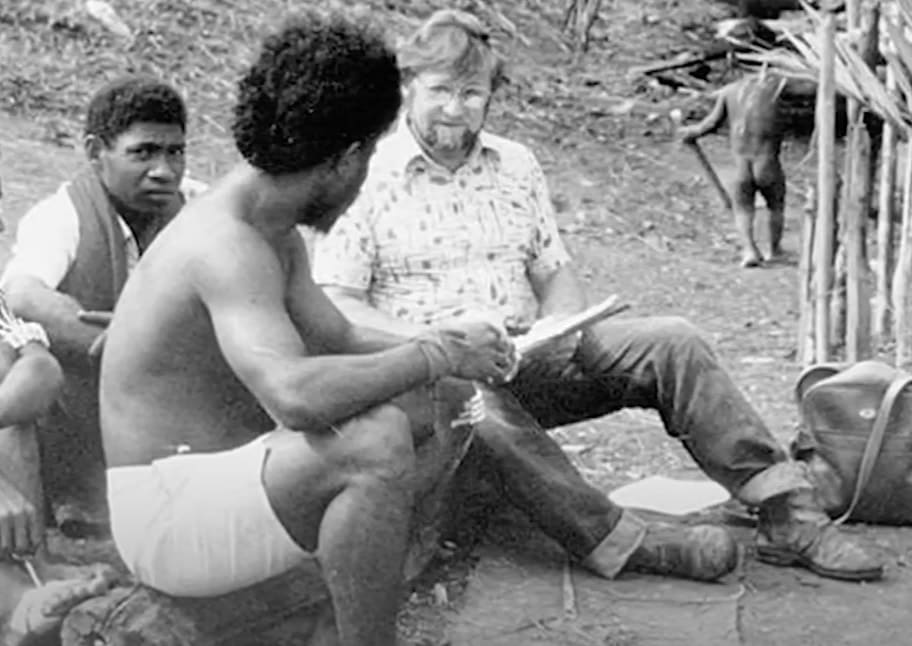

In 1978, he helped the Walpiri people in their fight for land rights in the Tanami Desert in the north of Australia, and was given the skin brother name of Tim Tchapanaka. He was behind a campaign to preserve Victoria’s Little Desert, and his expertise in bushfire ecology led to him working on the parliamentary inquiry into the 1983 Ash Wednesday fires.

He's been immortalised by having – in descending order of size – a glacier, hill and tiny rodent (Ningaui Timealeyi) named after him. This gave him the rare distinction of being able to claim that he was, indeed, both a man and a mouse.

In the 1970s, he was Channel Seven’s “Dr Tim” on the program This Week Has Seven Days, passionately educating children about ecology and conservation, and introducing the audience to many furry friends, which provided plenty of farcical moments (such as losing a koala in the lighting scaffolds).

Not surprisingly, he collected many plaudits over his lifetime, including a Robin Boyd Medal for Contributions to the Living Environment, a Victorian Education Award and a Commonwealth Coastal Custodian Order of Australia, as well as a UN Association Environmental Day Award. In 2008, he was honoured with a Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM), and was also the recipient of an Antarctic Medal from the Australian Antarctic Division after he became the first Australian scientist to circumnavigate Antarctica in winter.

In retirement

On retiring from Monash in 1986, aged 60, Tim only revved up the pace, setting up an environmental science faculty in Thailand, and consulting to the United Nations in the South Pacific.

In 1998, he moved to Coronet Bay, on the eastern shore of Western Port Bay in Victoria, with his third wife, Laura. Here he joined the Seagrass Partnership, throwing his energy into growing seagrass and thousands of mangroves in a bid to stem coastal erosion.

He enlisted 10 local schools to get involved with growing mangroves and planting them, and as a result became known as "Dr Mangrove". In 2017, shortly after he turned 90, the couple moved to South Australia to spend time with Laura’s family.

Throughout his career, Tim was drawn to the arts as much as to science. A keen amateur musician, he once jammed with Bob Dylan’s band in New York during a lecture tour in the US. He took up painting with Russell Drysdale’s teacher, and had a couple of successful exhibitions. For a while, he taught landscape painting at the University of the Third Age.

A lifelong fan of folk music, one of his favourite songs was the Kenny Rogers' classic The Gambler, which ponders the importance of knowing when to stay and when to run. As Tim once wistfully remarked, “I think I’ve made some good decisions in my life based on that philosophy.’’

Tim is survived by Laura, and daughters Jenny and Wendy from a previous marriage. A celebration of his life is planned for the future.

This article was co-authored by Kathy Evans and Renn Wortley from Monash University's Heritage and Tributes Unit, and was originally published on Monash's vale website.