There are currently about 18,000 Indigenous children across Australia who are living in statutory out-of-home care (OOHC), having been removed from their families. This is one-third of Australian children in care, or 11 times the rate of non-Indigenous children in care.

The trauma of removal is carried by the child, their family and community for life, and is often passed on knowingly or unknowingly to the next generation. Trauma and separation affect the development of the child, their feelings of self-worth and belonging, their sense of identity, and lifelong connections with family, community, culture and Country.

Despite this trauma extending beyond their time in care, what is rarely spoken about is the experiences, needs and outcomes of these Indigenous children once they reach the age of leaving state OOHC; 18 in all states and territories, bar the ACT.

There is currently some national focus on enhancing the pathways and outcomes for all young people when they turn 18 and exit care. The HomeStretch campaign, led by Anglicare Australia, is urging all Australian state and territory governments to increase the age of leaving care to 21.

Based on research that suggests that within one year, 50% of care-leavers will be either unemployed, imprisoned, homeless or have become a young parent, a range of notable supporters have joined this call.

Yet currently, only four states have adopted a trial of extension of care until 21 years (notably, ACT has already extended some support and care to 25). New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory have to date not introduced any extended care programs.

What happens when they turn 18?

The first national study to explore what happens to Indigenous children removed from care, once they turn 18, was conducted by Monash University, in partnership with SNAICC, the peak body for Indigenous children and families.

According to our research, approximately 1140 Indigenous young people aged 15 to 18 leave care across Australia annually. However, there are queries about the accuracy of this number. Alarmingly, it appears that the eight state and territory governments do not necessarily know the number of Indigenous children leaving care, where they go, or what happens to them.

There are some policies in place to support Indigenous care-leavers’ transition to independence, such as cultural plans that support connection to family and community while in care, and transition plans for life beyond care from the age of 15.

Yet, our research confirms previous data showing that many Indigenous children do not have meaningful cultural planning while in care, and that transition planning is often completed at the last minute, or not at all.

The result of this is that Indigenous youth are leaving care unsupported and unprepared to meaningfully and successfully reconnect with family, community and Country.

Often, Indigenous care-leavers self-place out of care at a young age, or experience a rushed, unplanned and unsupported transition to independence when they turn 18. This is in stark contrast to intact families, where young people often reside in the family home well beyond 18, and return multiple times until they establish independence.

The system is broken

Removed from family, having broken connections with community, and often living with non-Indigenous families or in residential units far from Country, Indigenous children transitioning from care are also experiencing the fallout of a system in crisis.

Funding for Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) in the leaving-care space is minimal to none, despite recognition of the unique cultural needs of Indigenous children. Victoria and Queensland are the only states that fund ACCOs to provide leaving-care services for Indigenous children ($1.16m in Victoria, and an undisclosed amount to one ACCO in Queensland annually), yet still not at a proportionate rate.

Service provision therefore falls to mainstream non-Indigenous organisations. Our research indicated that workforce issues abound within the sector. Access to Indigenous workers is minimal, Indigenous care-leaver engagement with non-Indigenous organisations is poor, and the services and programs that do exist often fail to provide culturally appropriate support.

The housing issue

There's a severe shortage of affordable and culturally safe housing for Indigenous care-leavers in urban, rural and remote Australia, resulting in a risk of transitioning into homelessness. Services reported examples of Indigenous care-leavers who, on their 18th birthday, contacted their service provider not knowing where they would sleep that night.

Indigenous care-leavers are being referred to temporary accommodation in adult homeless shelters or, in rural areas, are given tents to support rough sleeping. Limited housing options result in care-leavers self-placing or couch-surfing with family and community, who are often still living with unresolved trauma and disadvantage themselves.

Cultural insensitivities

As well as experiencing homelessness, Indigenous care-leavers may be leaving care with diagnosed or undiagnosed mental and physical health concerns. They may be experiencing difficulties with family relationships, and yet also be caring for siblings or extended family. They frequently have not been adequately taught independent living skills while in care, so struggle to care for themselves and others.

In some cases they're having children early, and then experiencing increased government surveillance due to their own history, meaning they have a higher risk of their own children being removed. They're also experiencing higher risk of youth and adult justice system involvement.

All these factors mean they need further support, yet our research found that Indigenous care-leavers are experiencing a culturally blind and insensitive system, leaving them vulnerable to a life of cycling through state and welfare systems that frequently fail to provide the culturally appropriate support they need to live a fulfilling and successful life.

We owe it to these children to do better

As a country, whose state and territory governments have statutory parental responsibility for these children, we have to do better for Indigenous children and young people. In order to do this, a series of changes need to occur.

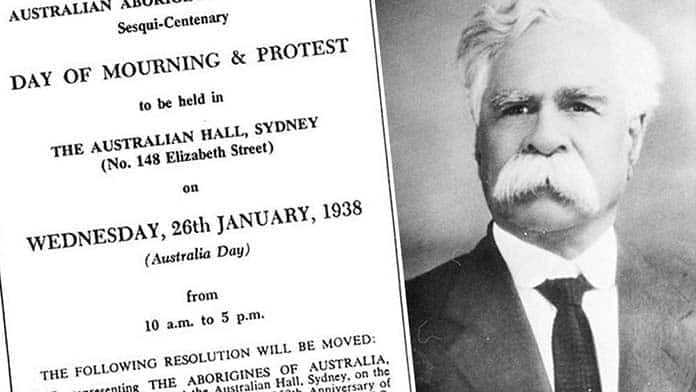

Firstly, as the very foundation for policy in this area, the OOHC and leaving-care sector needs to recognise the impact of historical government policies, and the ongoing intergenerational trauma and disadvantage shaping Indigenous communities today.

Secondly, a national commissioner for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and youth should be appointed. They should oversee a national benchmark for leaving-care policy and practice that supports Indigenous young people to remain in Indigenous communities.

In recognition of the need for accurate data to support ongoing improvements in this sector, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare annual child protection report should include reliable data on the number of Indigenous young people leaving OOHC, aged 15 to 21 years, and what happens to them in areas such as housing, education, health, and social and community connections.

All Indigenous young people leaving care should be able to access a proportionate housing allowance that allows them access to safe and secure housing.

And finally, in recognition that solutions for Indigenous people should come from Indigenous communities, ACCOs should be funded to provide all leaving-care services for Indigenous children. They should also be funded to design, generate, and apply quality and meaningful transition and cultural plans for all Indigenous care-leavers.

Connection to family, community and Country should be central to the lives of all Indigenous young people in care, transitioning from care, and beyond care, if they so choose.

Indigenous communities should lead the way

If, as a country, we're serious about "closing the gap" and supporting healthy Indigenous communities, we need to recognise the significant issue of ongoing intergenerational trauma that's created through the removal of Indigenous children into predominantly white service systems that fail to respond and care for them appropriately.

We need to recognise that service system responses need to be informed by the unique cultural knowledge that can only be provided by Indigenous communities and Indigenous-led organisations.

Indigenous youth leaving care are emerging elders and ancestors of the future. With appropriate resourcing and assistance, Indigenous communities can support Indigenous young people to lead healthy, fulfilling lives, and become the next generation of leaders for their communities.