For most of us during this pandemic, the focus has been to stay safely at home as much as possible. But for some, such as those who use opioids, whether prescribed (such as oxycodone) or illegal (such as heroin), the restrictions have brought unique challenges.

A significant problem for the health sector is that Australia has an escalating crisis with opioid-related disease and death rates. With COVID-19, this raises the potential for a syndemic – two epidemics at the same time – acting together to increase harm.

In Australia, an estimated 50,000 people are prescribed pharmacotherapy treatment for their opioid dependence. We believe about 100,000 inject drugs, and up to potentially 150,000 are dependent on prescription opioids in Australia.

For many, this means having to leave the house every day either to access drugs to prevent serious drug withdrawal, or to visit the pharmacy to receive a daily dose of their medicine, for people who are in treatment.

People who use illicit drugs such as heroin are also at heightened risk due to disruptions in the drug markets – historically, we’ve learned that unstable global circumstances have preceded the introduction of higher-potency and more dangerous drugs.

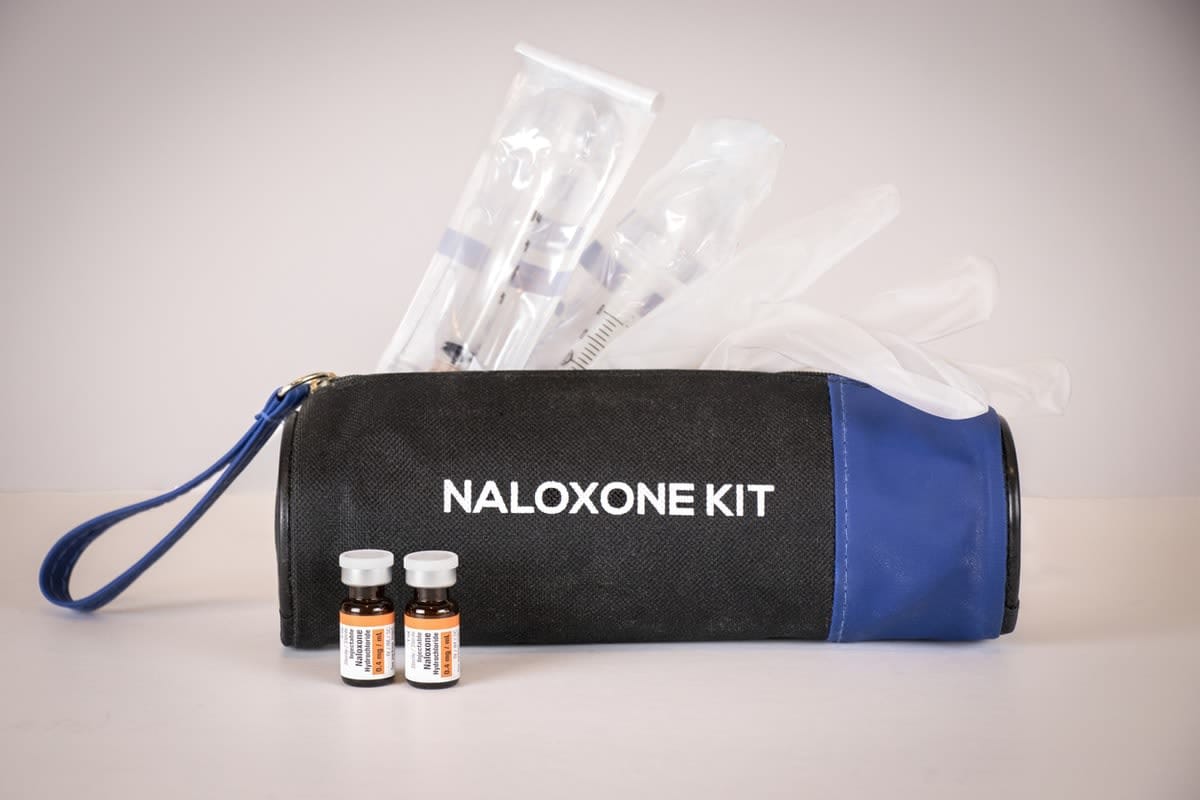

Measures such as physical distancing are critical to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Yet isolation may further increase the risks for those who use drugs. In the case of illicit opioid use (heroin), the presence of other people is an important protective factor in the case of overdose. When people are physically isolated, if they do experience an overdose, it’s unlikely that there will be someone there to call an ambulance, or administer the lifesaving medicine naloxone.

For many, the anxiety and stress associated with the current pandemic can escalate substance use. This has been widely discussed in relation to alcohol use, but these factors may equally affect those who use illicit drugs.

Illicit drugs markets will almost certainly be affected by COVID-19. There have been many changes in international and domestic travel, and shipping of goods, and these may affect drug markets in unprecedented ways.

For an island continent such as Australia, these effects may be amplified compared with countries with land borders. It’s too early to know exactly how these changes will affect drug supply – but anecdotal reports suggest prices are increasing, and drug purity may be reducing.

For people who are opioid-dependent, going without opioids either because drugs are unavailable or because treatment isn’t accessible results in significant withdrawal symptoms.

During the last significant change in the Australian heroin market, often described as a transition from a “glut” to a “drought”, some users switched to pharmaceutical opioids. With the increasing restrictions on pharmaceuticals through the introduction of prescription monitoring (which became mandatory in Victoria on 1 April this year), as well as other tightening of opioid prescribing, this is less likely to be a successful alternative.

“Supply shocks”, or dramatic changes in availability of a drug such as heroin or prescription opioids in other countries, have been identified as one of the contributing factors to the emergence of highly lethal synthetically manufactured opioids such as fentanyl. The sale of fentanyl (usually sold as heroin) led to a catastrophic increase in opioid-related deaths in the US.

Fentanyl is more concentrated than heroin, making it more likely to cause overdose, but also making it easier to ship internationally in smaller packages. If heroin becomes more expensive or harder to access in Australia, the emergence of fentanyl as a substitute is possible.

We’ve been monitoring the heroin market since 2017 to detect if there is evidence that fentanyl is being sold as heroin. We’re yet to see consistent signs of illicitly-manufactured fentanyl in Australia, but it’s critical we continue to monitor this and, if needed, provide appropriate harm reduction responses during this pandemic.

For people who are opioid-dependent, going without opioids either because drugs are unavailable or because treatment isn’t accessible results in significant withdrawal symptoms.

In extreme circumstances, this can be life-threatening. Withdrawal can lead to more risky substance use, and to increased crime where drug prices are increasing.

Complicating clinical assessment and management, the symptoms of opioid withdrawal may appear similar to a severe flu, including sneezing, runny nose, muscle aches and gastrointestinal symptoms. These symptoms may also contribute to the potential spread of COVID-19 among an already vulnerable population, making providing appropriate treatment a priority.

So what might help?

There are many proven ways to reduce the harms associated with opioid use. Expanding naloxone (an overdose reversal drug) supply is one evidence-based strategy to reverse opioid overdose. Some barriers to naloxone access have been removed, such as the need for a prescription, but there’s still much work to be done to urgently scale up supply in the community.

There are concerns about the availability of some essential medicines during COVID-19, and naloxone is no exception. A focus on the distribution of naloxone to those at greatest risk will remain critical.

Supervised injecting facilities are essential to removing the need for people to inject alone, and become more critical for the most vulnerable members of our community. These services ensure there is help at hand if an overdose occurs, as well as linking service users with primary healthcare and drug treatment services.

To support physical distancing, the capacity of these services may be reduced, placing pressure on staff and service users alike. Many who rely on these services are homeless, making advice such as hand-washing challenging in the absence of such services.

These drop-in services may represent the only contact people who use drugs have with healthcare providers. We need to keep these facilities open during the pandemic.

What about drug treatment during the pandemic?

As access to drugs becomes increasingly challenging, demand for treatment services may increase. Pharmacotherapy treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine have the strongest evidence for preventing mortality and reducing substance use.

Yet, there are pressures facing treatment providers during this pandemic as they adopt recommendations around physical distancing and telehealth. There’s also the risk that these healthcare providers become infected with the virus themselves and are unavailable for periods during the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving patients without care.

Drug treatment capacity is already insufficient for the many people who need it, with estimates that treatment places would need to double so that everyone who wants treatment can access it.

Pressure on our limited treatment places is likely to be increased by people being released from prisons, and from the introduction of prescription monitoring identifying those who need treatment for pharmaceutical opioid dependence.

Tensions also exist with the way that these treatments are delivered. Daily attendance at a pharmacy or other dosing point is not ideal during a pandemic. This places those in treatment at risk, and places additional pressure on, and and risk to, those working in pharmacies or other dosing points.

Access to treatment is the key

Irrespective of how treatment is delivered, individuals and the community will be safest if everyone who needs treatment can access it.

To reduce these risks and support continuity in treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, several Australian states are urgently making changes to support greater flexibility in how treatment is delivered. These changes include allowing stable patients to have more medication at home rather than attending pharmacies every day.

This is critical to reduce attendance at treatment sites, and is consistent with international practice, but the downside is that patients are now experiencing greater isolation without their usual face-to-face supports, and may be at increased overdose risk due to additional medication being at hand.

Consumer organisations are also working to support people who might want to seek treatment, or need support to stay in treatment with the many changes currently taking place.

These are extremely challenging times for all of us, including those people in our communities who experience addiction, and frontline professionals who provide treatment and other health services. Yet maintaining or expanding these services is essential if we’re to avoid a syndemic of opioid overdose and COVID-19.