What do Robin Boyd, Myer and The Age have in common?

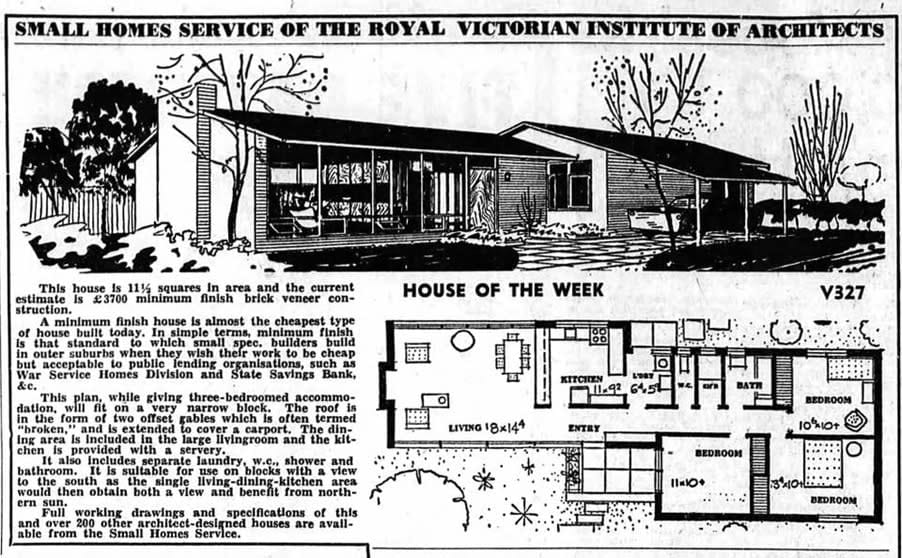

This unlikely trio of Melbourne icons joined forces post-war to deliver the Small Homes Service - compact, architecturally- designed homes meant for Melbourne's returned servicemen and newly-arrived migrants, built in spite of severe materials shortages post World War II, with the blueprints sold in Myer’s Bourke Street store for five pounds a piece.

Robin Boyd, one of Australia’s most influential and iconic architects and architectural critics, was the first director of the Small Homes Service. The house plans, designed anonymously by local architects, were published weekly in The Age, each with an accompanying explanatory column written by Boyd.

From 1947 to the late 1970s, Small Homes Service houses were built across Melbourne’s middle ring suburbs and regional Victoria. They were light and open, characterised by open planning and an economic use of space, and they brought modernist house design to the people of Melbourne - resulting in the now-distinctive mid-century modern style.

The Small Homes Service was indeed a ‘service’ - a popular vehicle through which good design could be democratised, with homebuyers of modest means given the chance to own a well-designed home, to be either self-built or built by a local builder on subdivided plots in ‘new’ suburbs like Beaumaris and Pascoe Vale.

It is estimated that up to 5000 homes across Victoria were built, possibly 15 percent of all homes constructed in the state at the time. The ‘service’ ethos is striking given our contemporary situation, with surging populations, and low affordability, even amid a 21st century property boom, where housing is often considered less of a public service and more of a private asset.

To prepare for next year’s centenary of Robin Boyd’s birth, and to learn what lessons the service can offer us today, Monash Masters of Architecture students set out to study the Small Homes Service, in particular leading a public call out for homes, artefacts and stories that people today might still have about the Service and Boyd’s role in it. These will contribute to an exhibition to be curated by Monash University Museum of Art director Charlotte Day and mounted at the Monash Art, Design and Architecture Gallery in mid 2019.

If a foundational aim of architectural education is to create the creative, critical, lateral thinking architects of the future, then Robin Boyd and the Small Homes Service are excellent subject matter for students to engage with. Not just a cult figure in local architectural culture, Boyd’s outstanding design skills, and engagement with contemporary architectural issues, combine to produce an exemplary model for today’s student, where architectural design can offer a positive alternative future.

The Small Homes Service arguably represented Boyd at his best - engaging in constructive critique, using the media to great effect, advocating for the common good, and making a difference in the world through design.

The new challenge

Today we face new issues that were less pressing in Boyd’s time, in particular the urgent need for environmental sustainability in buildings.

The Small Homes Service houses were modest, compact and used minimum means by necessity - they emerged during the post-war austerity period, where there was a real shortage of building materials. With a literal lack of bricks and mortar to build with, house design was forced to be compact and efficient.

Today, Australia’s homes regularly measure amongst the largest in the world, arguably far bigger than they need to be, with for-profit developers paying scant attention to the energy needed to service excess living areas, bedrooms and bathrooms. With rising energy prices also impacting on cost of living, compact and efficient homes with ‘just enough’ space make good environmental and economic sense.

There are new models of housing emerging today which might offer a contemporary counterpoint.

The Nightingale model, for example, offers high-density multi-residential housing in a way that is purposefully environmentally sustainable, financially affordable and socially inclusive. Whilst the Nightingale model is primarily a financial model, it also leads to certain design choices - including pared-back materials, fossil-fuel free heating and cooling and good solar orientation, leading to lower overall running costs and reduced environmental impact.

Read more: Challenging traditional housing models

With the thoughtful and efficient use of space and materials, good design saves money. Projects like the Small Homes Service and the Nightingale Model, amongst other contemporary housing ‘services’, show that people can experience better quality, more empowered lives when developers, architects and builders purposefully intend to provide quality homes for people, beyond offering speculative financial products for the investor market.

If you’re able to contribute to our research into the Small Homes Service – whether you or your parents purchased a house from Myer, you have any plans, brochures or photographs, or you believe you might live in one still standing today – please get in touch with Monash Art Design and Architecture.