On 7 April this year, a suspected chemical attack on the Syrian town of Douma was reported to have killed at least 40 people and injured up to 500, including women and children. Syria had made its chemical weapons capability known to the world six years earlier, with a public declaration of its intention to use them against any foreign assault. Under Saddam Hussein, Iraq waged chemical warfare against Iran and its own civilian Kurdish population, including the notorious 1988 attack on Halabja that killed 5000 Kurds.

Not even a common gas mask would have spared these victims a ghastly death. Widely used by the military to protect against mustard gas attacks in World War I, the technology in the masks, astonishingly, hasn’t been updated since.

When Australian soldiers based in Mosul were exposed to a low-grade chemical attack by Islamic State in April 2017, the Department of Defence realised a 21st-century solution was needed. Searching for someone with the capability to develop an improved canister, it approached Associate Professor Matthew Hill, the incumbent of an ‘experimental’ joint appointment between Monash University’s chemical engineering department and CSIRO.

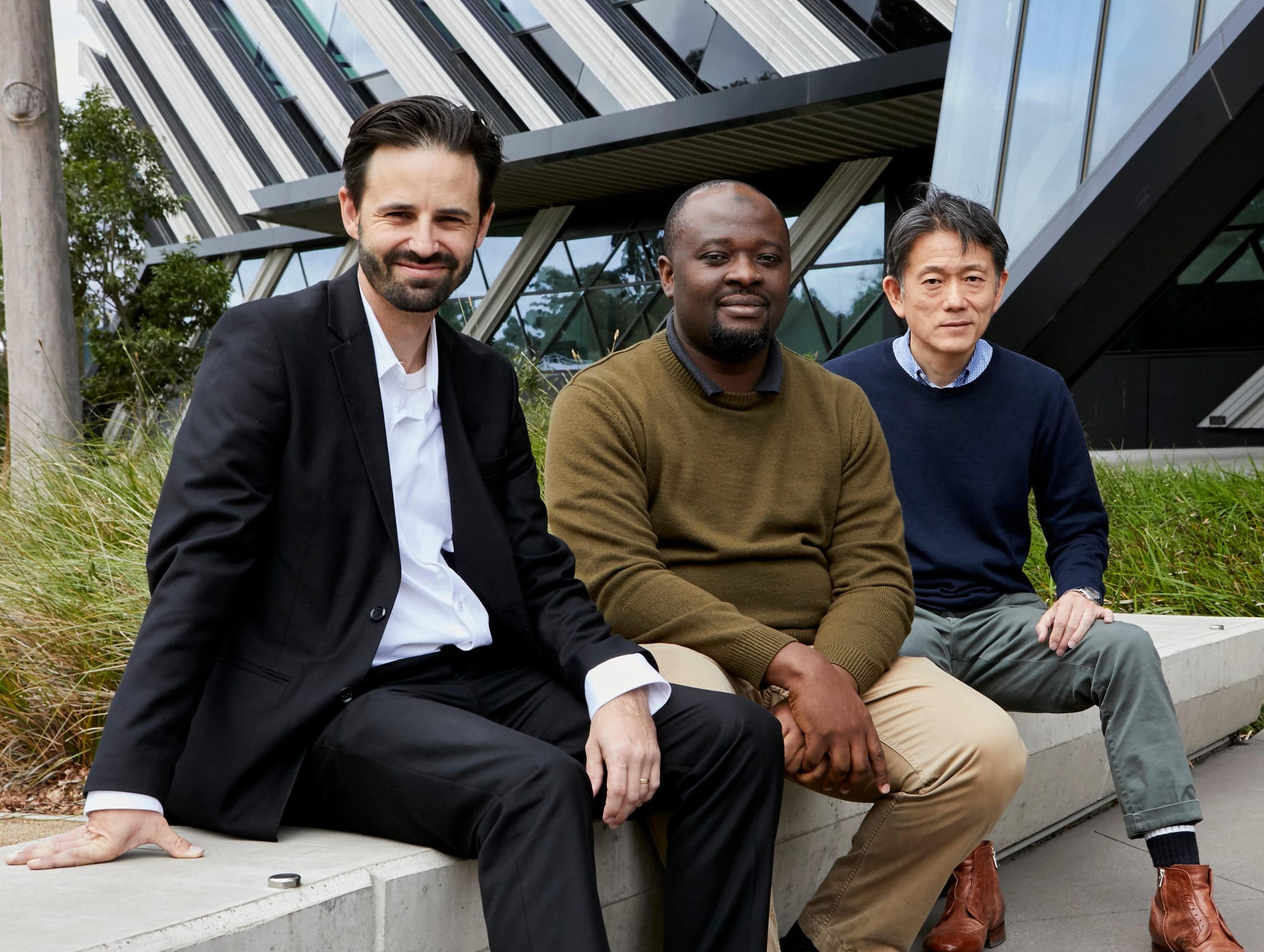

Hill – an ARC Future Fellow, 2011 Victorian Young Tall Poppy of the Year, 2012 Eureka Prize winner and 2014 Prime Minister’s Prize for Science winner – works 50-50 between the two organisations, taking full advantage of the research capacity of the University’s chemical engineering department and the industrial muscle of the nation’s science and technology lab.

“The current canisters in gas masks have been used by soldiers since World War I, and haven’t been improved since,” says Associate Professor Hill.

“They offer virtually no protection from common chemicals like chlorine and ammonia, so we’ve been commissioned to make a new canister that can. We’ve already found an improvement up to a factor of 40 using metal-organic frameworks. CSIRO would never have delivered this technology without the involvement of Monash, so we know this relationship is working.

''Once they’re on the market, they’ll be useful to anyone needing a safer gas mask, including our soldiers, but also firefighters, miners and construction workers.”

“The current canisters in gas masks have been used by soldiers since World War I, and haven’t been improved since.”

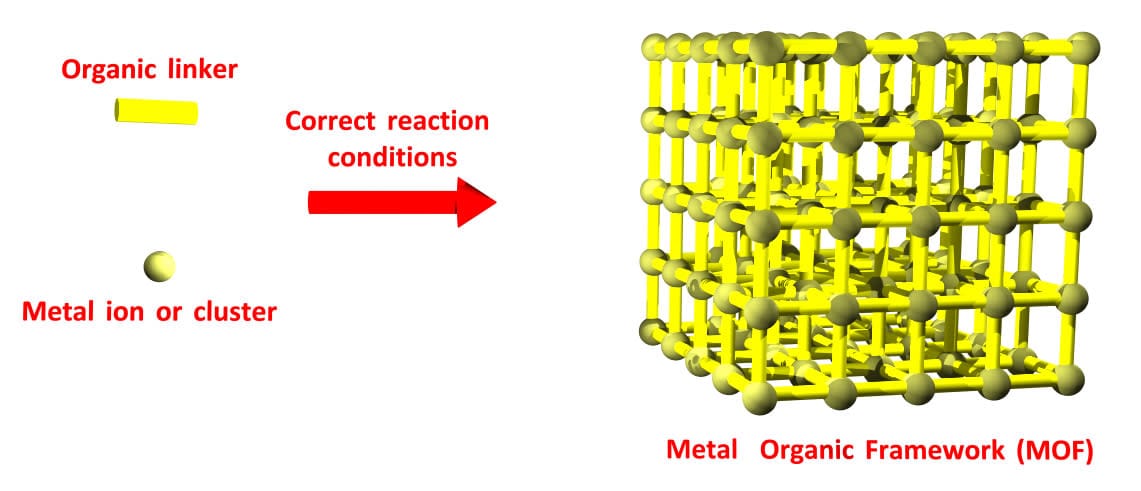

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) is the research linchpin in this innovative relationship. Highly porous materials that make it possible to store, separate, release or protect gases or liquids, MOFs have the largest internal surface area of any known material, and offer a real-world impact as vital as filtering toxic chemicals through a protective mask.

Associate Professor Hill is leveraging the know-how of engineers to make the science of MOFs applicable to useable products, and the 20-year-old MOFs technology is now being scaled up to produce up to 15kg of the material in pellet form – a global first.

“No one else around the world is doing this sort of fundamental science combined with process engineering at scale on MOFs,” says Monash’s head of chemical engineering, Professor Mark Banaszak Holl. “Applying engineering processes to the chemistry of MOFs while using the facilities of CSIRO, the Australian Synchrotron and the Melbourne Centre for Nanofabrication, all located within a short walk of each other, is something not available anywhere else in the world. This joint appointment, in this specific location, allows Matthew the opportunity to uniquely pursue MOF applications, like the improved gas mask canister, very successfully.”

Too small to not coordinate

The joint appointment allows for the pooling of resources within a limited local ecosystem. “Australia is such a small innovation system that we can’t have organisations undercutting each other,” says Associate Professor Hill. “Compared to who we’re competing against globally, we’re a very small country, and it’s much better to simply combine our limited resources.”

“Matthew couldn’t have done his incredible research on MOFs sitting isolated in a chemical engineering department somewhere,” says Professor Banaszak Holl.

“And it would also have been impossible to do it sitting purely in CSIRO, because of their industry focus. That’s the power of this type of joint arrangement offered in this particular engineering faculty. It’s very uniquely placed.” From CSIRO’s perspective, collaborating closely with Monash gives it direct access to high-quality PhD and postdoctoral students, allowing it to better deliver commercial solutions.

“For CSIRO, this partnership is ideal, as it allows both the in-depth study and commercial exploration of these exciting materials,” says Dr John Tsanaktsidis, the research director of CSIRO Manufacturing’s Advanced Fibre and Chemical Industries (AFCI) program.

Educating and creating future industry

Another project with clear significance, capturing carbon dioxide out of the air using MOFs, is also working its way into the marketplace.

Dr Munir Sadiq, who’s completing a PhD project under the joint supervision of Associate Professor Hill and Professor Kiyonori Suzuki from Monash’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, combined magnetic nanoparticles with MOFs to demonstrate the capture and release of CO2 at half the current costs. He’s now working in a team developing a prototype that’s attracting plenty of interest.

“I’m currently still using CSIRO’s facilities to complete the lab experiments needed to prove the technology is 100 per cent commercially viable,” says Dr Sadiq.

As an international student from Nigeria, he speaks highly of his experience within the collaborative and supportive network. “Without the joint appointment, it’s highly unlikely these two research areas would have come together to allow a project like this,” he says.

Technological entrepreneurship

Despite the progress, Associate Professor Hill believes Australia is still slowly building its capacity to foster this type of technological entrepreneurship. The country has the right people to make it happen, including Chief Scientist Alan Finkel (also a highly successful business innovator), CSIRO CEO Larry Marshall (described as a “serial entrepreneur”), even Prime Minster Malcolm Turnbull, who spent many years as a technology entrepreneur before entering federal politics.

In the research and development space, Associate Professor Hill has one key recommendation. “Universities are pushing for people to engage with industry. So I’d say to anyone who’d listen, don’t do it in a way that undercuts CSIRO, because that’s a zero-sum game for the country. We don’t need two people knocking on the same door asking for the same thing. While it might help one organisation’s bottom line temporarily, it takes it straight off the other one – who’s probably down the corridor in the same building anyway.”