Four years ago, a team of Monash psychologists began working on a smartphone app to help combat the growing spectre of anxiety and depression. Now there are two such apps, with one the winner of multiple awards. That app – MoodMission – has been downloaded 50,000 times with no paid marketing.

In June, the first of the two apps, MoodPrism, is being re-released into the market with added extras. “It’ll be fresher for the users,” says Adjunct Associate Professor Nikki Rickard of the Monash Institute of Cognitive and Clinical Neurosciences (MICCN). “It will feel squeaky-clean.” Once that new version is out, MoodMission may also be rebuilt and re-released, but that depends on funding. The apps were born of the frustration at many of the mental health apps on a flooded market having little or no real science built into them.

The MoodMission project began when Adjunct Associate Professor Rickard began supervising doctor of clinical psychology student David Bakker. He’d come to Monash from working as a mental health outreach worker. When he began his doctorate, Adjunct Associate Professor Rickard had just started work on MoodPrism, but soon her team of doctoral candidates began developing it and the subsequent MoodMission app together.

Complementary apps

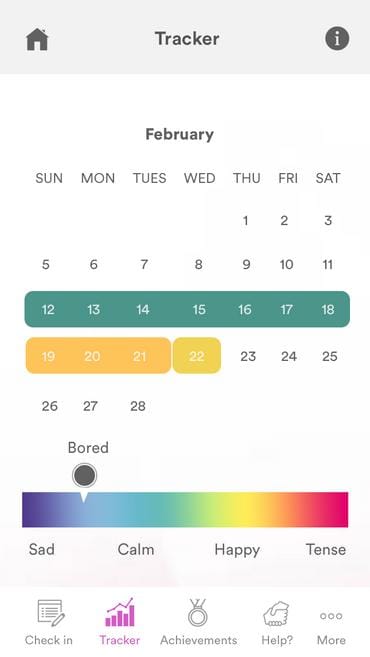

MoodPrism is primarily a research app, while MoodMission has clinical applications for the user. One grew out of the other.

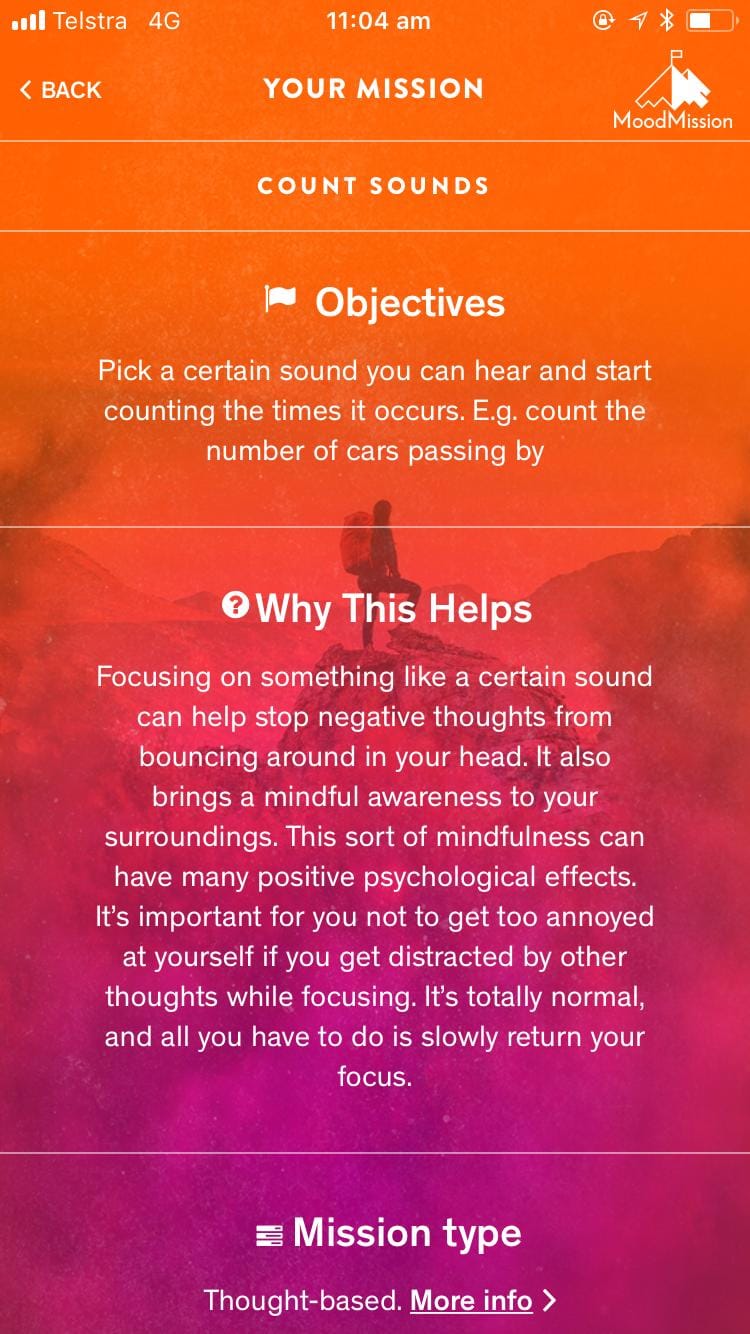

“Mental health apps weren’t providing focused, evidence-based support in a really hands-on way,” says Mr Bakker, who now also works as a registrar in a psychology clinic in Melbourne. “Some tried to engage patients in cognitive behaviour therapy [CBT] in unstructured ways, some would be great to use with a psychologist but not really so useful outside of therapy. There were none that answered the question: ‘Hey, I’m feeling anxious right now – what do I do?’ That’s how the idea for MoodMission got started.”

Adjunct Associate Professor Rickard says young people were a focus of the team’s work because they were at risk of leaving potential mental illnesses untreated. They also had high use of smartphones and instinctively knew their way around apps and in-phone games.

“We were interested in capitalising on this technology to fill a gap in mental health support,” she says. “One million people in Australia have depression and two million suffer from anxiety – and around one third of that total, especially young people, never seek professional help. The apps are for anyone, but there’s a focus on young people.”

She said that in general, the ‘Mood’ apps have three main aims:

Connect users – through MoodPrism – to relevant support services.

Raise emotional awareness in individual users. “People don’t seek help because they think they don’t need it,” she says.

Make them simple to use. “Some mental health apps can be daunting with a lot of details and homework. If you look at MoodMission, it’s intentionally built from very small units that are easy to use.”

MoodPrism was made with funding from the mental health body

prove their mental health, such as by walking or doing some physical exercise, calling a friend or meditating. It gives awards and badges, like a game. Users complete ‘missions’.

The app works,” says Dr Bakker. “We’ve seen changes in outcomes for wellbeing by using it for 30 days. It’s absolutely a success.”

MoodMission was initially paid for by crowdfunding, but the app’s rebuild was awarded funding by a Monash University accelerator program for startups called The Generator. Commercialisable features are being built into it.

Mr Bakker said some in psychology were hesitant to use or promote apps, but “this is an adjunct tool, a preventative tool and a low-intensity tool, but it’s definitely not the psychologist. It’s completely different. It’s all part of the pursuit to try help people with these sorts of issues.

“Apps can do things that psychologists can’t,” he says. “They can be with you while you’re having a panic attack on the bus, they can learn things throughout the day based on what actual thoughts you’re having while you’re experiencing depression or anxiety.”

Safety net

For Associate Professor Rickard, technology – or, at least, a phone app – can never replace one-on-one therapy. “The primary purpose is a safety net, filling the gap. We acknowledge that the majority of young people will not get one-on-one support, so one aim is to get them to realise they might need help. We’d like to show that some strategies might help, and linking with support might give them that one further step.”

Despite both apps’ popularity and the 2018 rebuilds, they’ll remain free of charge. “We always wanted it to be a free resource for vulnerable people,” Mr Bakker said.