Adani’s proposed Queensland coal mine has triggered the biggest environmental battle Australia has seen. Opponents say the mine will ruin the Great Barrier Reef and raise the global temperature. In the lead-up to the recent Batman by-election in Melbourne, Labor leader Bill Shorten was under pressure to withdraw federal support for the mine with his party struggling to keep the inner Melbourne seat from the Greens.

A lesser-known consequence of the battle over Adani is that fewer students are enrolling in mining engineering courses. Although the mining and resources sector accounts for two-thirds of the nation’s export income, young Australians don't see a future in the industry.

“People generally don’t recognise how important mining is to everything we do and use every day,” says Debra Stirling, a company director and former Newcrest Mining executive who chairs Monash University’s Mining and Resources Advisory Board. “You can’t function in a modern world without mining.”

Mines can't operate without mining engineers, who are required for regulatory (as well as practical) purposes. “Coal has clouded the issue, but we'll need every type of mineral in the future. For example, mobile phones alone use around 40 mined materials.” Ms Stirling says. “The growing demand for minerals and resources is population-based. People don't understand that mining and population growth go hand in hand. Mining isn't going to go away.”

Last year, 171 people were expected to graduate from Australian mining engineering courses. This fell to 98 this year, with the numbers predicted to fall further – to 69 in 2019 and 47 in 2020.

Last year, the World Bank released a report, The Growing Role Of Minerals And Metals For a Low-Carbon Future. It points out that green technology may well intensify the world’s need for material resources. Electric storage batteries will require aluminium, cobalt, iron, lead, lithium, manganese and nickel. Electric cars will also require lithium (and more copper than conventional cars), while hydrogen cars will need platinum. Demand is also expected to grow for manganese, silver, steel and zinc, as well as rare earth minerals. Mining will grow – and so will the need for recycling and environmental safeguards.

Mining companies are “very aware” of the looming shortage of mining engineers, and are trying to lure graduates with internships and vacation employment, Ms Stirling says.

“We're contacted by mining and resource companies every day who are looking for graduates. We could have placed our 2017 mining graduates 10 times over.

“Australia punches well above its weight on the global stage in the mining and resources sector,” she says. “Australian engineers in this industry are extremely well-regarded. They're among the best-qualified and most in-demand engineers in the world.”

Monash is the only Melbourne university to offer a mining engineering qualification. It's part of its multidisciplinary resources engineering degree program. The program also offers renewable energy engineering, oil and gas engineering, and geological engineering, and delivers course content from the science and business schools.

'We're contacted by mining and resource companies every day who are looking for graduates. We could have placed our 2017 mining graduates 10 times over.'

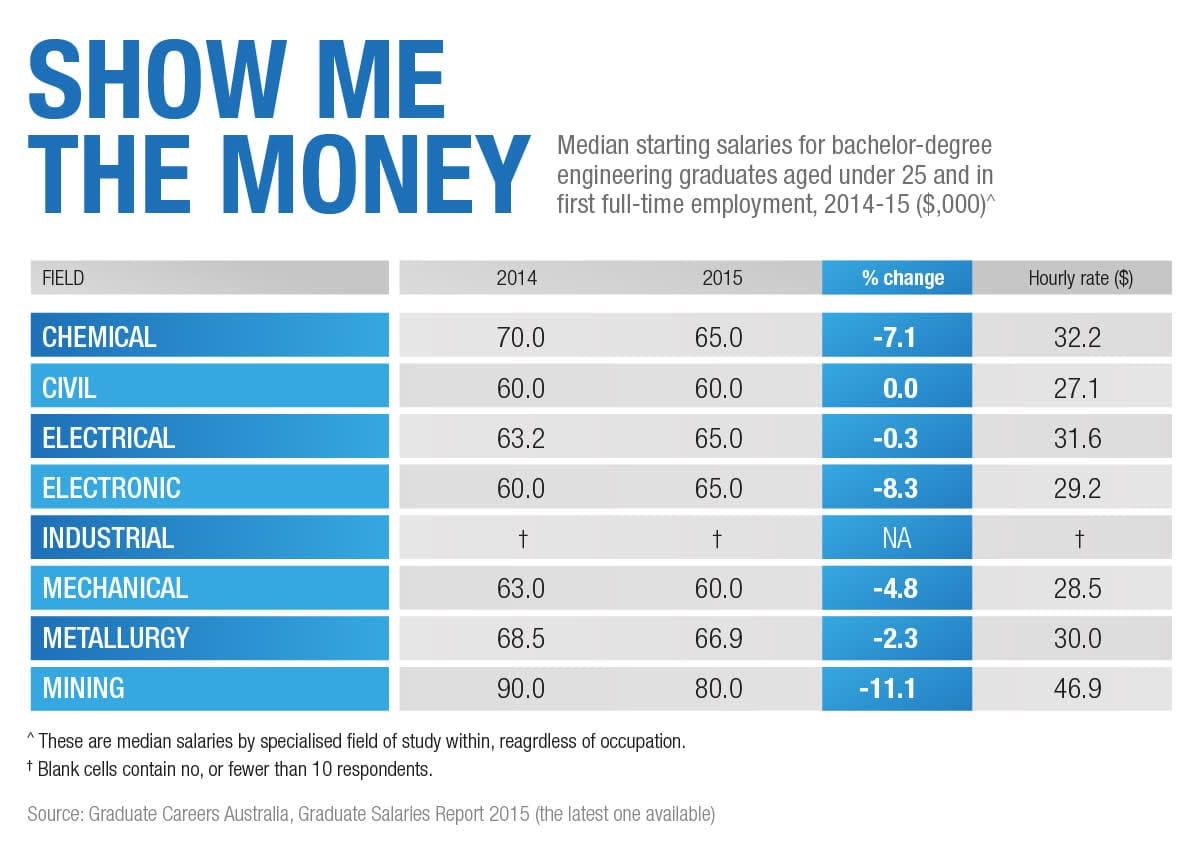

A list of employment statistics (1982 to 2015) from Graduate Careers Australia showed that mining engineers were the most employable engineers, with an employability index of 92.3. They're also the highest paid. Civil engineering followed at 88.8 per cent, and electrical engineering at 86.2 per cent.

Ms Stirling acknowledges that mining is subject to a boom and bust cycle, and that the industry is being disrupted by technological innovations such as driverless trucks and drone technology. “Many frontline positions such as truck drivers are going, but engineers and analytical positions are still in enormous demand,” she says.

At Newcrest, Ms Stirling was executive general manager, people and communications, with responsibility for a workforce of 20,000 over three continents. She describes mining engineering as “a complete job, in a way that many engineering jobs are not. Not only are you running operations, scheduling, projects etc, but you're also managing people from very early on in your career. You're engaging with the community and understanding environment and social issues.”

“This isn't a one-dimensional business,” she says. Mining and resources companies require “a social licence to operate”, and that involves taking “social and environmental responsibility” for the impact of their operations. “They're not Neanderthals destroying the environment and leaving vast, ugly holes everywhere. Communities in Australia and overseas would not allow this. People would be surprised at how innovative and responsible miners are.”