A telescope can reveal the beauty of the universe, such as the Moon’s craters, Saturn’s rings, and the glowing gas of the Orion nebula. But a telescope isn’t just for sightseeing – it's also a scientific instrument.

If you’ve just received a telescope as a present, then it’s probably better than any used by the Italian scientist Galileo Galilei (1564-1642). A small telescope with a modern camera can be more capable than professional telescopes from just a century ago.

You can use your telescope to see astrophysics in action, such as the planets travelling around the Sun, see how stars have different colours, and even detect worlds orbiting distant stars.

Read more: What to look for when buying a telescope

At the eyepiece

Look through the eyepiece of your telescope and you can retrace the beginnings of astrophysics.

Galileo only had a tiny telescope with a lens just a few centimetres across. Yet he mapped the Moon, saw Saturn’s rings, and discovered Jupiter’s four largest moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto – now known as the Galilean moons.

Galileo was also persecuted for advocating the theory that the planets (including Earth) orbit around the Sun, at a time when the popular belief was that Earth was the centre of the universe.

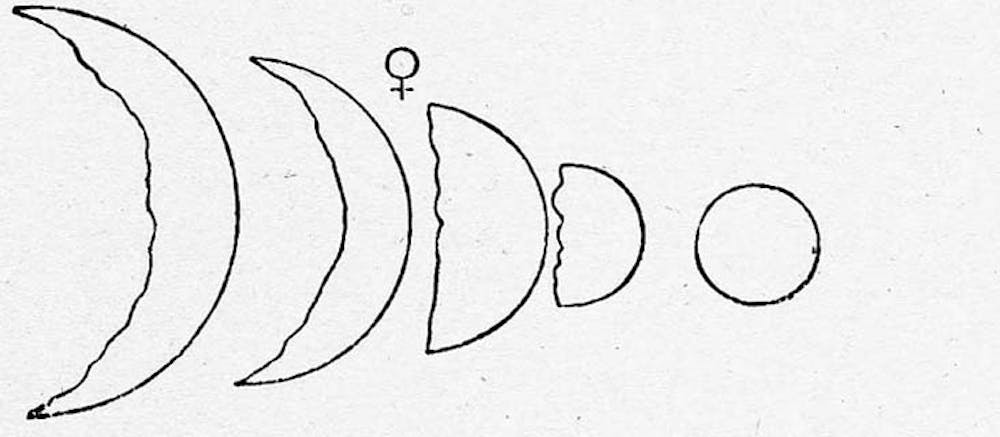

His observation of the phases of Venus are among his most compelling pieces of evidence that Earth and the other planets of our solar system orbit the Sun.

If the planets travel around the Sun, as Galileo believed, then sometimes the Sun will be (almost) between us and Venus, so we can view most of the daytime side of Venus. At other times, Venus will be between us and the Sun, and will appear as a larger (since it’s closer) crescent.

Venus is never too far from the Sun in the sky (indeed, it’s lost in the Sun’s glare during January 2018), and is only visible near sunrise or sunset. The phases of Venus, which resemble those of the Moon, can be seen with even a small telescope.

There are plenty of guides on how to find Venus (and other planets, stars, constellations, galaxies and so on) including Sky and Telescope, apps for Android and Apple devices, and the free Stellarium computer software.

Use any of these to find Venus, and then use your telescope to see the phases of the planet as Galileo did four centuries ago.

The lives of stars

Understanding the lives of stars was the biggest puzzle for astrophysicists during the early 20th century. One of the first clues is the fact that different stars have different colours, which tells us they have different temperatures.

Even without a telescope, you can see the red star Betelgeuse and the blue star Rigel in the constellation of Orion. Betelgeuse has a surface temperature of 3000℃, while Rigel’s surface is at 12,000℃.

Why do different stars have different temperatures? Measuring the luminosities of stars with different colours provides a critical clue. Look at open star clusters such as Pleiades and you will see that (with some exceptions) the brightest stars are blue.

Blue stars are often the most luminous (and most massive), and their high temperatures result from the rapid fusion of hydrogen into helium. Some blue stars are 100 times as bright as the Sun.

These stars live for just millions of years, as they're using their hydrogen fuel so rapidly. In contrast, some dull red stars may live for tens of billions of years.

What about the exceptions – the very luminous stars that are red, such as Betelgeuse? Some stars have run out of hydrogen in their cores, and instead fuse hydrogen in shells and/or fuse helium in their cores.

These stars can become enormous in size but have (relatively) cool surface temperatures. These red giants are also approaching the end of their lives.

Strange new worlds

So far your telescope has been used for simple observations of stars and planets. With the addition of some more equipment you can use your telescope to detect planets around distant stars.

To do this you need a good digital camera, the ability to track a star for a few hours, and some free software for your computer.

The first planets orbiting other stars were detected in the 1990s and now thousands of such worlds are known. Some of these planets orbit stars that are 100 times fainter than the unaided eye can see, and such stars are easily seen with small telescopes.

Read more: Google’s artificial intelligence finds two new exoplanets missed by human eyes

But what about the planets? Well, at predictable times planets pass between us and their stars, making the stars dim by about 1 per cent. You can’t see that tiny change in brightness with your eye, but you can record it digitally.

If you can take digital images of a star with a planet and several neighbouring stars, then you can use computer programs (such as OSCAAR) to measure how the star dims relative to its neighbours. You can thus see the passage of a distant world around its star.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Michael J. I. Brown receives research funding from the Australian Research Council and Monash University.